http://www.beyondcalligraphy.com/clerical_script_part_2.htmlhttp://www.beyondcalligraphy.com/what_is_calligraphy.html

History of Japanese

Calligraphy - Part 1

The history of Japanese calligraphy begins with importing the Chinese writing system, namely kanji (漢字, which in Japanese means “characters of Han China”), in the early 5th century C.E., although Chinese characters were first appearing in Japan on various items brought from China starting with the beginning of the 1st century C.E.

At that point, the Chinese writing system was fully matured and developed. There were approximately 50 000 kanji in circulation, 5 major styles of calligraphy and numerous sub-styles.

Since Japanese linguistics and grammar are quite different from Chinese, the necessity of fitting a writing system to a completely new language raised a serious practical problem. Nonetheless, it has led to creating unique calligraphy styles that are exclusively used in Japan, such as Kana (かな).

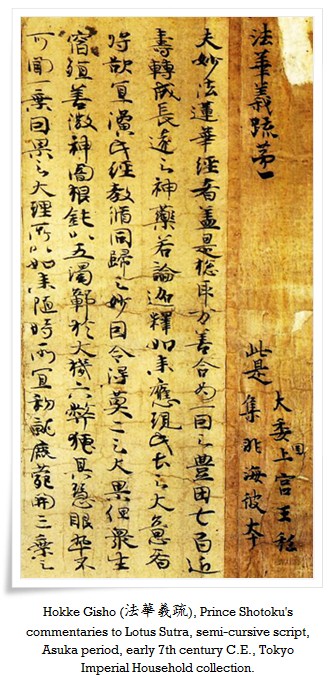

During the Asuka (飛鳥時代, 538 - 710 C.E., although dates may vary based on different historical events being considered) and Nara (奈良時代, 710-794 C.E.) periods, copying Buddhist sutras was already a very popular practice, which greatly contributed to strengthening the appreciation and fascination with Chinese culture. At that time Japanese calligraphy was especially influenced by writing styles developed during Chinese Jin (晉朝, 265 - 420 C.E.) and Tang (唐朝, 618 – 907 C.E.) dynasties. This general trend was called karayou (唐様, lit. Tang style), which means “Chinese style”.

One of the great admirers of Buddhist teachings was the Japanese prince Shotoku Taishi (聖徳太子,, 574–622), who promoted its philosophy, and also built several major temples. He was the one who strengthened the popularity of shakyou (写経, hand copying of sutras), that further led to the development of calligraphy in Japan.

At this point, Japanese sho (calligraphy) was still deeply influenced by Chinese masters like Wang Xizhi (王儀之, 303 – 361). A vast amount of works were based on his style, all the way until Heian period (平安時代, 794 - 1185 C.E.)

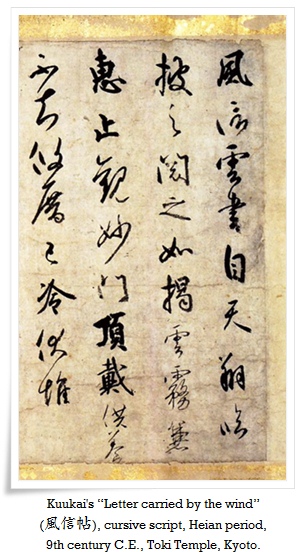

The 10th century was a time of significant change in Japanese calligraphy. It is when Ono No Michikaze (小野道風 894–966, who is also known as Ono no Toufuu) introduced a fresh approach and the first truly Japanese style, called wayoushodou (和様書道, lit. “Japanese style calligraphy”). This trend however, was originally brought into being earlier on by the famous Buddhist monk and outstanding calligrapher Kukai (空海, 774- 835), who gained the sacred Buddhist name “the great (Buddhist) teacher” (弘法大師, Koubou Daishi). At this point it became acceptable for Japanese literature and calligraphy to finally deviate from Chinese aesthetics.

Ono no Toufuu, was considered one of the 10th century sanseki (三蹟, lit. “three brush traces”), along with two other individuals Fujiwara no Sukemasa (藤原佐理, 944 – 998) and Fujiwara no Yukinari (藤原行成, 972 – 1027).

Michikaze was so talented, that he was accepted to serve at the imperial quarters at the age of 27. He was a diligent calligrapher and his style was naturally powerful yet easy for the soul to appreciate. The other two of the sanseki, greatly contributed to developing further what Michikaze started.

A good example of work that not only displays Michikaze’s potential and artistic capacity but also how versatile his style was, is Gyokusen Jou (玉泉帖), a kansubon (巻子本, lit. “a rolled book”) with poems that were composed during Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907) in China. It is also a great masterpiece of wayoushodou, full of surprising rhythm, extremes in proportional scaling, wide variety of line strength, slow brush traces suddenly rushing through paper, mocking the changes of the emotional states of the artist.

Wayoushodou was based on sougana (草仮名, cursive kana) and Kana (かな, calligraphy script), which derive from manyougana (万葉仮名, “kana of ten thousand leaves”). It was a result of pursuing aesthetics native to Japan, by members of the upper class.

Manyougana was a remedy for grammatical differences between Chinese and Japanese languages which this new writing system had to face. Manyougana was then applied as grammatical fillings, postfixes, particles, etc. It was nothing else than kanji used purely for phonetic reasons.

Imagine how difficult it must have been to read texts with some kanji playing semantic roles and others reflecting only sounds (though they bore their own abstract meanings anyway, like any other Chinese characters). Around the 12th century there were approximately 1000 kanji in use as manyougana.

Sougana is nothing else but manyougana in Cursive script, thus in sousho (草書). Simplified sougana gave birth to modern hiragana (平仮名) which is used in a unique Japanese calligraphy script - Kana. .......

Main styles of Chine…

Main styles of Chine… East Asian calligrap…

East Asian calligrap…